History Taking

- Uncovering the Story

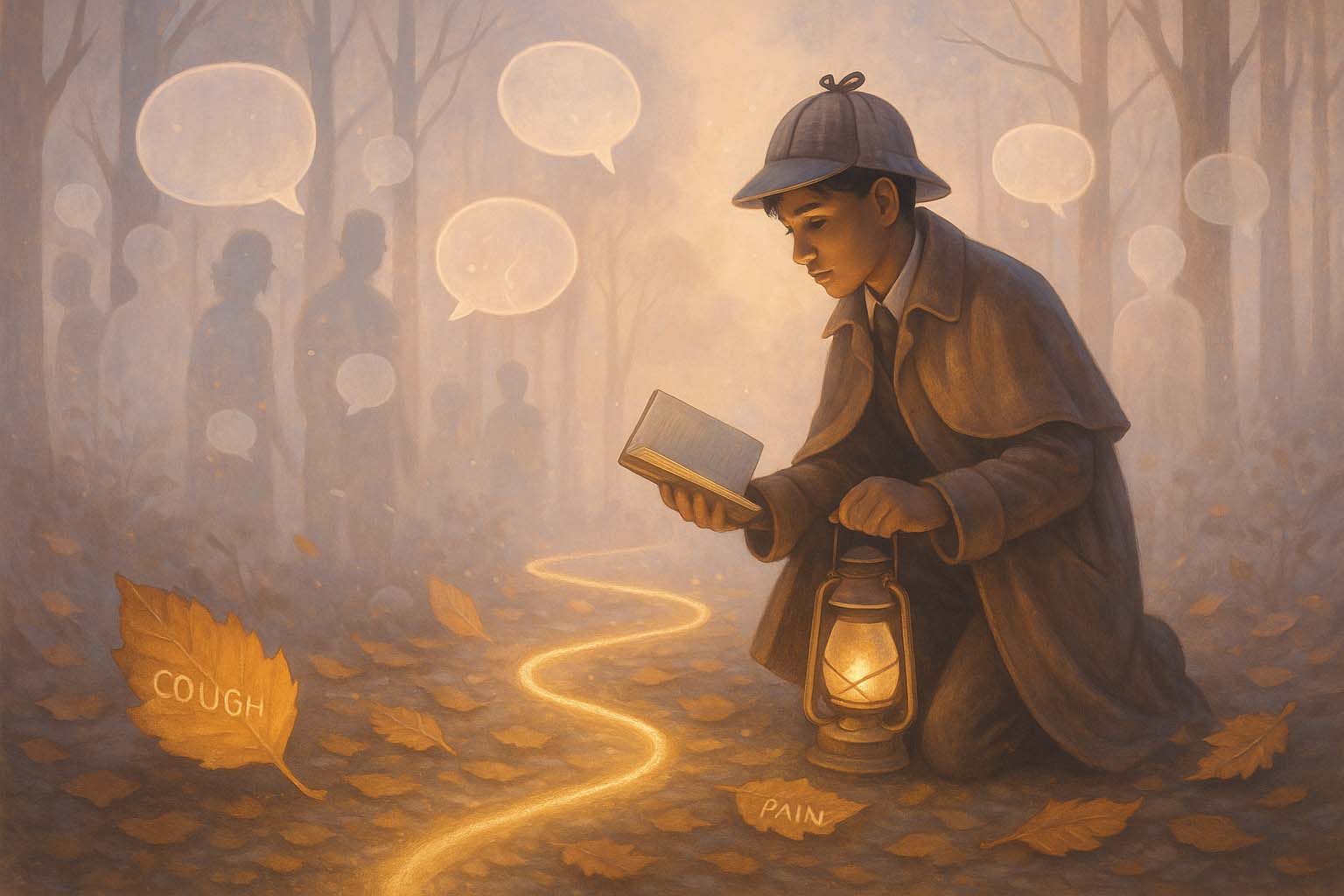

🕵️ The Detective’s Guide to Medical History-Taking

Welcome to Medlock Holmes’ School of Clinical Sleuthing, where every patient encounter is a mystery waiting to be solved. Your most powerful investigative tool? The medical history. Much like a seasoned detective, you begin by collecting clues, constructing timelines, and listening for subtle inconsistencies. In this world of clinical deduction, the art of history-taking is your first—and often most revealing—step.

🧩 Presenting Complaint: The First Clue

Every case begins with the presenting complaint—the headline on the front page of your investigation. Why has the patient come in today? Is it chest pain, a severe headache, shortness of breath, or unexplained fatigue? This first clue sets the tone and directs your early hypotheses.

But headlines can be misleading. The true story often lies beneath, and it’s your job to read between the lines.

📜 History of Presenting Illness: Constructing the Timeline

Once the presenting complaint hands you the headline, the real detective work begins. The history of presenting illness (HPI) is your opportunity to investigate the who, what, when, where, why, and how of the symptom at hand. Just as a sleuth interrogates the scene of the crime, you’ll use curiosity and structure to trace the full arc of the patient’s experience—gathering not just what happened, but how it unfolded.

Think of the HPI as the case’s chronology. You’re reconstructing events minute by minute, hour by hour, day by day. Was the pain sudden or gradual? Has it changed in character? What makes it better? Worse? What has the patient already tried—and did it help or hinder?

This is where storytelling and structure meet. Good detectives don’t just listen for facts—they listen for patterns, pauses, and emotional tone. The timeline must be coherent, but also flexible enough to catch the details that don’t fit the expected plotline.

🧠 The Gradual Puzzle: A Headache Case

A 22-year-old student presents with a headache. “When did it start?” you ask.

“Around exam time,” they reply vaguely.

You press further: Is it sharp, dull, or throbbing? Is it one-sided or all over? Any visual symptoms, neck stiffness, or sensitivity to light? You learn they’ve had similar episodes before, triggered by lack of sleep, heavy screen use, and dehydration—classic migraine. But if the patient adds, “It’s the worst headache I’ve ever had,” you switch tracks. Now you’re investigating for a subarachnoid haemorrhage, meningitis, or even cerebral venous thrombosis.

A good detective remains alert for red flags hiding in the folds of a familiar story.

❤️ The Sudden Strike: A Chest Pain Case

A 58-year-old smoker arrives with central chest pain that started while mowing the lawn.

You begin your questioning like clockwork: When did it begin? What were you doing at the time? Did it radiate anywhere? What was the quality—crushing, sharp, burning? Was there shortness of breath or sweating? Has it happened before?

The words “crushing,” “left arm,” and “cold sweat” ring alarm bells. But suppose the pain is sharp and worsens when breathing in—now you’re considering pleuritic causes, like a pulmonary embolism or pericarditis. A detective never assumes the suspect; they follow the evidence.

🥴 The Murky Onset: A Gastro Case

A young woman presents with vague abdominal discomfort. You ask about timing, location, and associated symptoms.

“It’s just… there,” she says, gesturing vaguely.

You zoom in: upper or lower? Right or left? Constant or cramping? Any changes in bowel habits, recent meals, travel, nausea, or urinary symptoms?

Suddenly she mentions she hasn’t had a period in six weeks. Now you’ve turned from mild gastritis to a potential ectopic pregnancy. The plot has thickened. A careful HPI helps you avoid jumping to conclusions—and ensures you don’t miss a life-threatening twist in the story.

🧠 The Principles of Great HPI Gathering

- Anchor in Time: When did it all begin? And what’s happened since?

- Shape the Symptom: Site, onset, character, radiation, associated symptoms, timing, exacerbating/relieving factors, severity (SOCRATES or similar).

- Tread the Timeline: Walk chronologically through the symptom’s evolution. How is today different from yesterday? Or last week?

- Listen for Emotion: Frustration, fear, confusion—what matters to the patient may lie between the words.

- Stay Open to the Unexpected: Not every case ends where it began. Be ready to switch lenses.

By crafting a detailed and dynamic history of presenting illness, you transform the vague into the specific, and the ordinary into the revealing. It’s not just about ticking boxes—it’s about unfolding the patient’s story in a way that allows the truth to emerge.

As Medlock Holmes reminds all junior sleuths: “The clue you almost missed is often the one that solves the case.”

🗂️ Background History: Exploring the Archives

Once the current case has been described, your attention turns to the archives—the patient’s broader background. These chapters from the past often contain important clues that shape your current understanding.

🔍 Past Medical History: Recurring Characters and Old Cases

Think of this as reviewing past case files. Chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, asthma, epilepsy), previous surgeries, or prior admissions all shape your current investigation. A patient presenting with chest pain and a history of hypertension, for instance, immediately shifts your diagnostic compass.

🧬 Family History: Tracing the Lineage

Family history is your genetic fingerprinting. Conditions like heart disease, cancer, diabetes, or autoimmune disorders often run in families. Uncovering these patterns can be crucial—especially in cases like early-onset hypertension or migraines.

🧭 Social and Personal History: Mapping the Scene

A great detective understands the setting. What’s the patient’s occupation? Living situation? Exercise routine? Alcohol, smoking, or recreational drug use? Stress levels? These lifestyle factors influence not just risk but management strategies—vital for presentations like chest pain, weight loss, or anxiety.

🧳 Travel, Exposure & Occupation: Hidden Clues in the Environment

Recent travel, sick contacts, or occupational exposures can be pivotal in cases of fever, diarrhoea, or unexplained infections. A returned traveller with fevers? Consider malaria. A schoolteacher with a cough? Consider tuberculosis or viral illness.

🔎 Symptom-Specific Background Focus

Depending on the symptom, certain background elements become especially important:

- Headache: History of migraines? Visual disturbances? Use of oral contraceptives? Recent trauma?

- Chest Pain: Smoking, hypertension, cholesterol, family history of early heart disease?

- Acute Abdominal Pain: Surgical history, medication use (NSAIDs, laxatives), dietary triggers?

- Syncope or Seizures: Previous episodes? Family history of epilepsy? Witness accounts?

Tailoring your background questions to the clinical context sharpens your diagnostic edge. This is where the detective starts to narrow down suspects and rule out the red herrings.

🧶 Stitching It Together: The Clinical Narrative

When done well, history-taking is not just a checklist—it’s narrative construction. You’re gathering fragments, listening for inconsistencies, following threads of plausibility. You’re not just collecting data—you’re uncovering motive, mechanism, and meaning.

By the end of a good history, you should be able to summarise the case in your own words, not just theirs. The timeline should be clear. The setting understood. The potential culprits narrowed. Now you’re ready to enter the next phase: the physical examination.

🕯️ Final Word from Medlock

So don your metaphorical deerstalker hat. With each patient, you are not just a recorder of symptoms, but a detective of the human condition. And as you refine your craft, you’ll find that most diagnoses—like the best mysteries—are solved not by fancy tests, but by a sharp ear, a curious mind, and a well-told story.